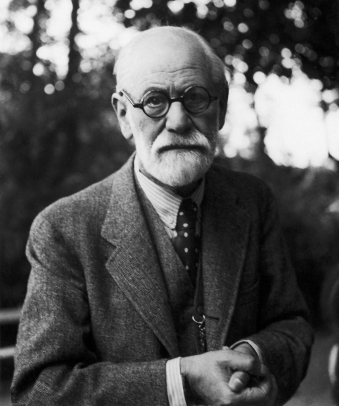

2017 is the centenary of the publication of Sigmund Freud’s Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis, one of his most popular and widely translated works. Curiously, this is also the 90th anniversary of the publication of The Future of an Illusion, Freud’s attempted debunking of “religion.” This latter book was and is his most controversial book, at least among Christians and Jews, many of whom ever after looked upon this “godless Jew” (as he wryly called himself) as an implacable enemy.

2017 is the centenary of the publication of Sigmund Freud’s Introductory Lectures on Psycho-Analysis, one of his most popular and widely translated works. Curiously, this is also the 90th anniversary of the publication of The Future of an Illusion, Freud’s attempted debunking of “religion.” This latter book was and is his most controversial book, at least among Christians and Jews, many of whom ever after looked upon this “godless Jew” (as he wryly called himself) as an implacable enemy.

That book, alas, gave too many Christians an excuse not to read Freud and engage with him. Indeed, many disdained Freud based merely on summaries (invariably tendentious) of one or two parts of this book or some other work of his, missing the whole picture. Protestant, Catholic, and Orthodox Christians felt that Freud, along with Marx and Nietzsche—whom, collectively, the French Protestant philosopher Paul Ricœur dubbed the “masters of suspicion”—had to be ignored or even denigrated as an enemy of faith.

But to ignore Freud in particular is, I have long contended, a big mistake because he offers crucial insights that Christians, no less than anybody else, very much need. Fortunately, not all Christians have been so defensive around Freud. I have recently discussed elsewhere certain Western Christians who engaged with Freud and the later analytic tradition. But what about the Christian East?

Eastern Orthodox engagements have been relatively fewer, but in the last three decades there have been at least four noteworthy engagements, all of them positive (but not uncritically so). (I leave aside earlier and sometimes more superficial engagements from, e.g., Nikolai Berdyaev, who died in 1948.) Lila Kallinich, in an article in the St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly published in 1989, wrote a full-throated defense of the psychoanalytic tradition, noting that “God gave us Freud, and for some reason, however obscure, He made Freud the major proponent of spiritual tools to which we as Church originally laid claim. So Freud is ours, and ours too is psychoanalysis.”

Those spiritual tools originally part of the Church were, as Kallinich suggested, and as I have documented in more detail elsewhere, often to be found in the hands of Evagrius Ponticus, whose writings on the logismoi—the disordered thoughts—form a diagnostic system with a therapeutic intent which I have long regarded as psychoanalytic avant la lettre. Evagrius came up with his insights based on his long experience of listening to the many people who sought his spiritual counsel, even as he tried to hide from them in his desert monastery. As the historian Peter Brown has nicely put it, “The lonely cells of the recluses of Egypt have been revealed, by the archaeologist, to have had well-furnished consulting rooms.”

In 1996 the Orthodox therapist J. Stephen Muse wrote positively of how “psychoanalysis and Christian faith, life, and worship, authentically engaged, promote awareness of the hidden motives of the human heart.” A little later in the same essay, he notes how “psychoanalysis can be an important and powerful ally in the search for religious maturity.”

Muse’s essay was published in Personhood: Orthodox Christianity and the Connection Between Body, Mind, and Soul (ed. J.T. Chirban, 1996), a collection that also contained an essay by the well-known Greek Orthodox scholar Christos Yannaras. He argued in “Psychoanalysis and Orthodox Anthropology” that, following the example of the Fathers of the Church, who were not scared to learn from the scientists of their day, so too Orthodox Christians today should not be afraid to learn from Freud and, in a particular way, from his controversial French follower, Jacques Lacan, on whom Yannaras focuses. Lacan’s most famous observation was that “the unconscious is structured like a language:” Yannaras uses this to argue that psychoanalysis and Orthodox Christianity are similar in both believing that the human person is ultimately called into being by the language acts of others—“Let us create mankind in our own image.” Yannaras also notes, approvingly, that psychoanalysis can be useful in a clinical setting to help us overcome “the self-torture of narcissistic egocentrism.”

Finally, and most recently, Petru Cazacu has written a book, Orthodoxy and Psychoanalysis: Dirge or Polychronion to the Centuries-Old Tradition? (Frankfurt: Peter Lang, 2013), which was the author’s graduate thesis in pastoral theology at the University of Balamand. The book seeks to explore the work of Basil Thermos, “a well-known Greek Orthodox priest, [and] a child and adolescent psychiatrist.” Cazacu does this in order to sift what of psychoanalytic and psychotherapeutic insights and methods will be useful, especially with and for seminarians and clergy. He’s careful to note that being psychologically healthy is not the same thing as being holy, but that the lack of the former among clergy will severely impede their ability to lead people to the latter.

Freud, of course, was not concerned with holiness, but he was concerned with things that any pastor or other Christian cares about: the liberation of the human person from the shackles of illusions and self-imposed suffering. Both analytic and Evagrian therapies seek to move people ex umbris et imaginibus in veritatem.

Since Freud’s death in London in 1939, the psychoanalytic tradition has developed far and wide, often in very different directions from what Freud laid out. Among his descendants today, it is the British analyst Adam Phillips whom I regard as the most interesting. Like Freud a non-practicing Jew, Phillips has nonetheless the most to offer Eastern Christians, for there is in Phillips a deep and abiding strain of apophatic thinking I have found nowhere else. (This apophaticism is also treated, albeit from a different clinical perspective, in David Henderson’s recent book, Apophatic Elements in the Theory and Practice of Psychoanalysis: Pseudo-Dionysius and C.G. Jung.)

In more than a dozen books over the last quarter century, Phillips has been trying to move us beyond rigid ideological thinking, including that often propagated by psychoanalysts themselves when they try to be masters of the mind, offering definitive “professional” solutions to our problems. Psychoanalysis works best, Phillips says, when it reminds us that “too much definition leaves too much out.” Eastern Christians, with our long traditions of apophaticism and mysticism which shy away from excessive definition of God and much else, will be at home here with this approach.

It is especially in his book Missing Out: In Praise of the Unlived Life that Phillips makes his “apophatic” turn, that is, his turn to not knowing or, as he frequently puts it, to not “getting it;” to letting go of the desire, one might say, to eat the fruit of the tree of knowledge of good and evil: “Omniscience… is the enemy, the saboteur, of satisfaction” (134). We need to become accustomed to not getting it, and to asking ourselves this question: “In which area of our lives does not knowing, not getting it, give us more life rather than more deadness?” (80).

Not knowing, not getting it, is, I submit, very much what the apostle has in mind when he says we walk by faith and not by sight. Not having all the answers—which Phillips wishes to encourage in analysts and analysands alike—is something Christians should be accustomed to. We do not help ourselves by pretending to a certainty that God has not given us.

None of this should be taken as a plea for mystification rather than mystery, for an undoing of doctrinal definitions where they have legitimately been promulgated by the Church to clarify controverted questions. It is, rather, a plea to remember that the very nature of doctrinal definition is that of a boundary drawn solely to warn us off the dangerous area (“Beware of Mines!”), leaving us otherwise free and unmolested to wander, to roam, to explore. Doctrinal definitions free us so that we can come more intimately into communion with that truth by which alone we are free, Jesus Christ.

Jesus, the very Word and true image of the Father, comes to liberate us from our false images and idols. In this light, as Ricœur recognized more than forty years ago, Freud’s Future of an Illusion should be welcomed by Christians, because its intent is a purifying one. Freud was a good iconoclast, showing us that we need to destroy false images of God that we often project onto Him, so that we may at last come face to face with Him as He really is, freed from our neurotic images of Him. The end of psychoanalysis, then, is—for Byzantine Christians at least—the ability, finally and freely, to sing, self-forgetfully, as we do at Matins: “God is Lord and has revealed Himself to us. Blessed is He who comes in the name of the Lord!”

Adam DeVille is associate professor and chairman of the Department of Theology & Philosophy at the University of Saint Francis in Fort Wayne IN, and editor-in-chief of Logos: A Journal of Eastern Christian Studies. He holds a PhD in Theology from the University of Ottawa and St. Paul University. His published works include Orthodoxy and the Roman Papacy: Ut Unum Sint and the Prospects of East-West Unity. He blogs at Eastern Christian Books.

Pingback: ORTHODOXY AND FREUD: IS A CONVERSATION POSSIBLE? by A.A.J. DeVille – VIRTUAL BORSCHT

Pingback: THE CATHOLIC SEX ABUSE CRISIS: HOW CAN ORTHODOXY HELP? by A.A.J. DeVille | ORTHODOXY IN DIALOGUE

Pingback: Lent, fear of freedom, and love of slavery - Catholic Daily

Pingback: Lent, fear of freedom, and love of slavery - Catholic Mass Search

Pingback: On the Relationship between Psychology and Theology | The Russell Kirk Center

Pingback: Surveying the often tense relationship between Christianity and psychoanalysis – Catholic Mass Online Search