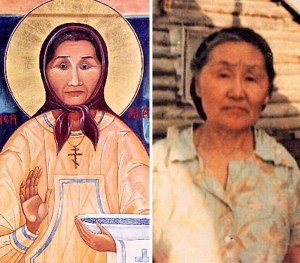

St. Olga of Kwethluk

(1916-1979)

Katherine Kelaidis’ head-scratcher, Xenophobia in the Cloak of Progress: How English Liturgies Hurt the American Orthodox Church, appeared on Public Orthodoxy on March 12. Her readers have registered their overwhelming dissatisfaction over the past nine days by assigning it 1.7 stars out of 5. This is one of the lowest I’ve seen since Public Orthodoxy started including Readers’ rating at the top of each article. Kelaidis’ rating elicits a response as much as the article itself. I write as one who, as both layman and priest, has spent most of my long Orthodox life in parishes that worshipped exclusively or primarily in the English language, but who also has extensive experience attending parishes that worship in Slavonic, Ukrainian, and Greek.

The author’s anti-assimilationist stance seems sharply at odds with her full-throated embrace of assimilation seven years ago. There, she begs her sister Orthodox who choose to cover their heads in church to follow Yiayia’s assimilationist, women’s liberationist lead under the influence of television. (See my response.) Here, she argues for the small-t tradition of retaining “heritage languages” liturgically over against the capital-T Tradition of delivering the Faith in the vernacular wherever the Church finds herself in the divine economy to draw the world into Christ’s net. Christ our God has sent down the Holy Spirit upon each of us, from highest patriarch to lowliest yiayia no less than upon the original disciples on the day of Pentecost, to make us most wise fishermen and fisherwomen, we all doing our own grand or small part in word and deed to make the Orthodox faith accessible to all.

Kelaidis begins her essay thus: “Orthodox Christianity in the United States is an immigrant church. That is to say, it is a church primarily brought to the United States by 20th- and 21st-century immigrants and still largely populated by them and their descendants.” The Hellenocentrism and flawed historicity of this statement, coupled with the conclusions the author draws from it, raise a number of objections.

First and most obviously, in an apparent conflation of Orthodoxy with Greek ethnicity (not unusual of Greeks, in my experience), Kelaidis ignores the fact that the Orthodox Church arrived and thrived on North American soil through the missionary efforts of the Russian Church beginning in the 18th century, almost a century and a half before the Greek emigration. The first American Orthodox weren’t immigrants at all, but native Aleuts. The Russian mission to Alaska gained momentum in the 19th century, several decades before the Greek emigration, with the creation of an Aleut alphabet based on the Slavonic, the compilation of a primer of Aleutian grammar, and the translation of key Scriptural and liturgical texts into the Aleutian language. Any photo of 21st-century church life in the OCA’s Alaskan diocese will show virtually all clergy and laity to be indigenous Alaskans. They bury their dead under pre-Christian spirit houses topped with three-barred crosses. They have their own seminary. The OCA recently canonized a Yup’ik clergy wife, St. Olga of Kwethluk (1916-1979).

Indeed, tsarist Russia’s Kazan Theological Academy performed the task of translating Scripture and liturgy into every indigenous language encountered in the Church’s expansion across the Eurasian steppes and the Bering Strait into Russian Alaska.

The see of the Russian diocese moved from Sitka to San Francisco in 1872, and to New York City in 1903, in a visionary project to evangelize America in the primary language of the nation. There was no thought of creating Slavic ghettoes where liturgy itself was consigned to be a repository of “heritage languages.” In conformity with the most basic of all ecclesiological canons—to whit, that a given geographical territory be placed under the care of a single bishop—all Orthodox immigrants to the US and Canada were shepherded by priests under the omophorion of the Russian bishop of New York City. The provision of vicar bishops who spoke the various languages of the growing Orthodox emigration was well underway when church life was turned upside down in the US and Canada by the Russian Revolution of 1917.

Second, Orthodoxy qua “immigrant church” in the US and Canada predates the Greek emigration by decades. East Slavs who now call themselves Ukrainian, Carpatho-Russian, or Rusyn, as well as Romanians, arrived in large numbers in the latter half of the 19th century. In the US, they worked the coal mines and steel mills; hence, the proliferation of Orthodox churches in places like Pennsylvania. In Canada, they homesteaded the untamed prairies; hence, the proliferation of Orthodox churches in Manitoba, Saskatchewan, and Alberta. Some Canadian communities erected their first church while their families lived in holes in the ground covered with straw and branches. Sometimes an unwary cow crashed through and landed in the middle of supper. As a priest, I pastored the children (my parents’ age), grandchildren (my age), and great-grandchildren (my kids’ ages) of the original Romanian and Ukrainian pioneers who founded my parishes and built the first churches. Two of my very oldest parishioners came from Romania with the original pioneers as infants in arms.

The exodus of Slavic-American Uniates into the Orthodox Church under the initiative of St. Alexis Toth began in the closing years of the 19th century.

Third, it’s unclear what difference Kelaidis imagines between the importation of Orthodox Christianity by immigrants and colonizers from Europe and that of every other form of Christianity in North America. We’re all descendants of immigrants, whether our DNA arrived in the new world in the 1400s or the 2000s. By this metric, all we Christians of whatever stripe belong to immigrant churches.

Kelaidis puts her mind-boggling incomprehension of the matter on full display when she writes:

This new reality must become part of the linguistic debate in the Orthodox jurisdictions in America. It is incumbent upon us to challenge the ways in which we have, either intentionally or accidentally, contributed to xenophobia by embracing English as a “default” language and by advancing arguments that call into question the belonging of anyone in the United States who does not use English as their sole or principal language.

[…]

In the long term, this should also mean that no priest can be ordained in America without proficiency in a second language. This is all to say, that after decades of insisting in the language of assimilation that no non-English linguistic competence was necessary to participate in Orthodox communities in America, it is time to reverse course and make linguistic diversity and a resistance to linguistic assimilation a core part of our identity in the United States.

To this I respond:

- Using the vernacular in worship and preaching has nothing to do with “assimilation,” or “progress,” or “xenophobia,” or “Trumpism.” It has everything to do with making disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the Name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit. I’m not sure what universe Kelaidis inhabits, where anyone gives a hill of beans over what language people speak at the coffee hour.

- I’ve attended Greek parishes (not just one) at some length, both for Sunday and weekday Liturgies. These parishes have bled and continue to bleed their young couples and singles, teens and children, even on Pascha. The congregation of very old people murmurs with excitement when some 13-year old boy gets behind the microphone and recites the Lord’s Prayer in Greek during the Liturgy. They count this a success with the young people. He’s one of three kids in church that Sunday morning. Forget about evangelizing the non-Greeks in the neighbourhood or even serving lunch once a week to the homeless. These parishes fail to evangelize their own, as each successive generation feels less and less connection to a “heritage language” that they don’t understand and never hear spoken at home anyway.

- The “mother church” of Toronto’s Greek parishes is virtually wrapped around by Toronto Metropolitan University. Yet the parish’s only outreach to the students was to try to sell them souvlaki during the first week of the semester one year. Not a single book or pamphlet on the Orthodox faith was to be found alongside the souvlaki. When the sisterhood president lamented to me that they hadn’t turned a profit, her eyes opened wide with sudden comprehension when I said, “Good! I’m glad. The Lord didn’t bless it. Young people are spiritually hungry. The Orthodox Church has what many of them are hungry for. It sure ain’t souvlaki.”

- By way of contrast, Toronto’s ROCOR cathedral holds divine services exclusively in Slavonic and preaches exclusively in Russian. For the massive, ever-growing congregation of new arrivals from Russia, these aren’t “heritage languages,” but living languages of daily life and prayer. Most of the adults, and even a large number of the children, speak no English. I have seen it take upwards of an hour to distribute Holy Communion with two priests and two Chalices. In a church with no pews, the people are crammed like sardines in a can on a normal Sunday. Weekday Liturgies bring in almost as many people as on Sunday if it’s a great feast. On minor feasts, more people attend than the Greek churches see on a Sunday. The cathedral has a clear pastoral mandate to minister to Russian-speaking immigrants of every age from newborn to nonagenarian. The Greek churches have no such mandate, or else they would be overflowing with young Greek-speaking immigrants with their Greek-speaking children.

- Kelaidis’ call for all candidates for the priesthood to be proficiently bilingual suggests, once again, the conflation of Orthodoxy in America with the Greek Archdiocese. Why should an OCA priest, or the majority of AOCA priests, be obligatorily bilingual—unless they be encouraged to learn Spanish to evangelize the nation’s growing influx of Latinos?

Just as Kelaidis’ article has no clear endpoint, neither does mine. The matter should entail no ambiguity: the Church worships and preaches in the actual vernacular of the congregation, not in its “heritage language” for old times’ sake.

Let our readers continue the conversation.